Tariffs on Southeast Asian countries, as well as further action against Chinese products, could have the most obvious impact on the US solar industry. The president announced a 46% tariff on products from Vietnam, 36% on Thailand, 24% on Malaysia and 49% on Cambodia as well as a further 34% levy on Chinese goods.

The European Union (20%), India (27%), South Korea (25%), Laos (48%) and Taiwan (32%) were among the raft of other countries that Trump dubbed the “worst offenders” hit with tariffs above the 10% universal rate.

The tariffs would be paid by US companies importing goods from the relevant countries, which they are likely to pass on to end consumers through price increases.

Southeast Asia

The US sources more of its solar modules, cells and other components from Southeast Asia than any other region. Cells may be of particular importance.

The ongoing antidumping and countervailing duty (AD/CVD) tariffs which have increased the price of solar cells entering the country from Vietnam, Cambodia, Malaysia and Thailand, have already decreased the volume of imports from the four countries compared with 2024, according to the US Department of Commerce (DOC).

Despite this, Southeast Asian countries and South Korea still account for the overwhelming majority of solar cells entering the US to supply its growing module manufacturing industry; over 12GW in 2024. These may now become more expensive.

Tariffs are sometimes viewed as tools to support domestic manufacturing against imbalanced international competition. While the US has previously found Chinese companies guilty of circumventing its trade barriers by relocating parts of their supply chain to Southeast Asia and “dumping” solar products at unfairly low selling prices, it is still broadly reliant on imports from a supply chain dominated by those same companies.

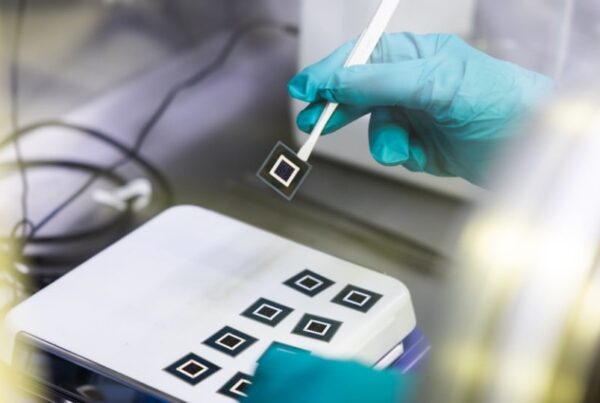

Though the US has established around 50GW of PV module manufacturing capacity, according to the Solar Energy Industries Association (SEIA), the components needed to supply those factories (including cells) are still mostly imported from Southeast Asia. Cell production lags significantly behind module manufacturing capacity.

Ultimately, the Chinese companies operating in Southeast Asia may relocate their capacity and production expertise to other, less-harshly hit regions.

Tariffs will be a key discussion topic at the Large Scale Solar USA conference later this month in Dallas.

Could India capitalise?

With a 27% “reciprocal” tariff, India got off relatively lightly in Trump’s trade bombardment.

The country’s solar manufacturing capacity has boomed in recent years; data from the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) showed that module production capacity had doubled and cell capacity tripled between March 2024 and March 2025.

With a comparatively low premium on importing to the US, Indian products could become attractive to US module and cell importers in the future as the country builds out its manufacturing base.

Vibhuti Garg, director, South Asia at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis said that, in the short term, Indian manufacturers who were already shipping products to the US would take a hit, though she said “some of that supply can be diverted to meet domestic demand” in India.

In the long term, Garg said the “very high” tariffs imposed on other countries like China would allow Indian solar products to remain competitive in the US market. “There could still be demand for [Indian PV products in the US] if they are serious about meeting their targets on clean energy,” she said.

PV Tech will follow this story with industry reactions and developments as it progresses.