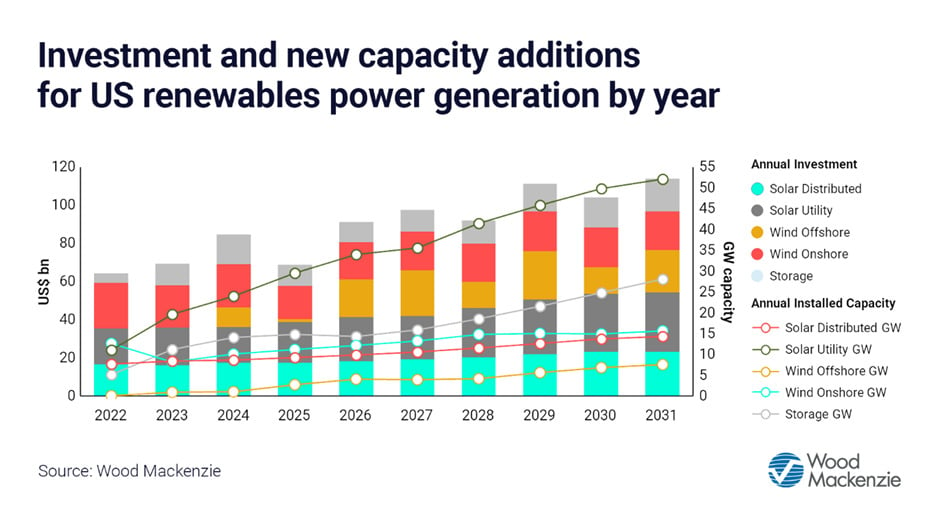

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) is set to boost investment into US renewable energy deployment and manufacturing from US$64 billion in 2022 to US$114 billion by 2031, according to research from Wood Mackenzie, though a mismatch between solar deployment demand and domestic manufacturing capacity may see the sector’s domestic profile lag behind.

Though growth is expected across all renewable energy sectors, the analysis firm’s latest report, ‘Boom time: what the Inflation Reduction Act means for US renewables manufacturers’ posits that solar PV manufacturing will face more headwinds than onshore and offshore wind.

Principal among these is the current cost of US-made modules and components compared with Southeast Asian counterparts. WoodMac said that US manufacturing costs can be as much as 32% higher than imports and that, as it stands, sourcing module components in the US would raise the overall cost stack of domestic panels by an additional 17%.

The US is on track to install an additional 73GW of solar PV through November 2025, according to a recent analysis by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. Current domestic manufacturing capacity, though growing, will not come close to fulfilling that demand. As of December 2022, 22GW of new cell and module manufacturing capacity had been announced since the passing of the IRA.

WoodMac said in its report that module expansion plans now total 45GW of supply, though upstream cell, wafer and ingot capacity is far less established. A significant announcement from Hanwha Qcells earlier this month for a US domestic ingot-to-module supply chain speaks to the potential for upstream to be established, but it is unlikely that it will expand in time to meet current demand.

The anti-dumping and countervailing duty (AC/CVD) probe by the Department of Commerce could see strict tariffs imposed on Southeast Asian imports. This could help domestic manufacturing become cost-competitive, but President Biden’s two-year waiver on the tariffs has pushed this benefit back.

“With such a small solar manufacturing base currently in the region, juxtaposed against substantial forecasted growth in solar additions, fully meeting US solar needs with domestic equipment will be more challenging than other sectors,” said Daniel Liu, principal analyst at Wood Mackenzie.

The key components of the IRA that will drive investment are the advanced manufacturing production credits (AMPC), a tax credit for US-made assets, and the domestic content requirement (DCR) tax credit which rewards developers for using US-made products.

The AMPC has the potential to account for 29% of manufacturing costs, were an integrated supply chain to be established.

To be eligible for the DCR, project developers must use 40% made-in-America equipment on anything developed before 2025, rising to 55% after 2026. Whilst in the long-term this offers a good incentive to developers to use US products, WoodMac points out that qualifying for the credit after 2026 will be difficult without the use of US-made modules, which, as established, are currently far more expensive than imports, raising equipment costs by up to 27%. The DCR offers a 5% return on equipment costs on a net present basis.

The AMPC will help to close the gap between domestic and imported component costs, and along with the AC/CVD tariffs the IRA may be capable of making domestic product the most viable in time.